But it wasn’t a useless lesson. My thoughts are like the cat meowing for his breakfast, insistent and annoying. If you feed the cat in response, you’ll only encourage it to come back and be more insistent and more annoying the next time. These thoughts are best ignored or noted for later consideration, but that doesn’t immediately stop them from being insistent and annoying. I’ve developed an impressive ability to ignore the cat’s meowing, I can do the same for obsessive thoughts.

With my recent third cancer diagnosis, a painful stent in my urinary tract, a bump in my chest from the chemo port, and a case of chemo brain, my head has turned into crazy cat lady central. I simply can’t count the number of obsessive thoughts meowing away. Frankly, it’s enough to aggravate my allergies.

The most basic question I face in my life today is which cats do I want to feed? Which ones do I want to encourage? Here’s one that’s making a contended purring sound, he gets some kibble.

I’ve written previously about my dire diagnosis and atrocious prognosis. It’s good to be mindful of it to the extent that it keeps me motivated to stick with the treatment plan and seek out anything that can help me limbo under the low line of the survival curve. But beyond that, it’s not good dwell on it. We’ll keep this cat in a crate in a corner of the basement. That’s not animal cruelty, it’s just a metaphor. No actual cats are being kept in crates in my basement.

The cat I’ve chosen to adopt, call my own, and allow to freely roam around the house is called Mizuno, the marathon cat. He was written out of “Cats”, the musical, as his name was difficult to rhyme and sing. Tough break. But I digress.

I fully believe that my treatment will be effective and allow me to train for and run a marathon. If anything, the biggest obstacle between me and my second marathon is overuse injuries to my joints, as that has scuttled several previous attempts. Since my diagnosis I no longer have a time goal, just a desire to finish a marathon no matter how long it takes. That will hopefully translate into less joint stress. In fact, I plan to walk as much as run in this marathon.

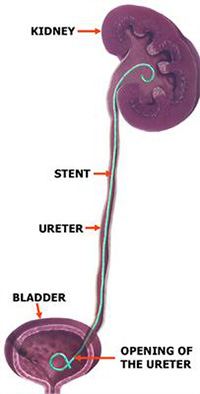

It’s a Jedi mind trick I play on myself. Cancer is not viewed as a deadly disease (though it still is), but treated as a mere obstacle to my marathon goal. It’s a problem that must be solved. The tumor in my bladder must be shrunken to the point where the stent can be removed, so that I can resume long runs without pain and blood in my urine.

Being able to envision a meaningful future is key to keeping my sanity. It’s the difference between enduring cancer treatment, or simply suffering medical torture. Laying around the house most of the day watching Netflix may sound like a lot of fun to some people, but it’s leaving me quite uninspired.

There are parallels between marathon training and chemotherapy. Marathon training involves periodic long runs which are stressful to the body and cause it significant damage. Following each long run it is necessary to rest and have shorter, easier runs while the body recovers from and adapts to the long run.

Chemotherapy is similar. Instead of a long run, the body is stressed by having poison injected into it which causes significant damage. Following each infusion is a period of rest, gentle exercise, and recovery. Where chemotherapy and marathon training diverge is that the body generally gets stronger and more fit during marathon training, while with chemotherapy the body is beat further and further down with each cycle. Oncologists would make bad marathon coaches, as they would definitely overtrain their athletes.

Mizuno, the marathon cat is the cat I choose to feed. May he live long and have many kittens, including PET, the complete remission kitten, Peaks, the hiking kitten, Splinter, the firewood cutting kitten, and Jobber, the return to work kitten.

Routine Update

Chemotherapy is going as well as can be expected. While I still have pain, it’s now generally responsive to pain medication and hasn’t gone past the end of the pain scale since chemotherapy began. As this cancer can’t be tracked through blood tests, there’s no way to tell if this is due to tumor shrinkage, or just my urinary tract settling down after having the stent inserted. I’ll be scanned again at some point during chemotherapy, and that will show what the tumors are doing. There will be a lot of scanxiety associated with that scan I’m sure.Side effects are the usual suspects of nausea and digestive issues and pain, all manageable with pills. There’s also fatigue, which is exaggerated by the previously mentioned pills, and can’t be helped but to get a bit of exercise and plenty of rest.

Last week, just hours after my most recent chemo infusion I was running around at the indoor track, though with lots of walking because of that annoying stent. This wasn’t an act of superhero powers, but rather a combination of my fitness from before treatment began combined with dexamethasone keeping the chemo side effects at bay. Let me put it this way: Cancer and its treatment have reduced me from running 10 miles to walking 2 miles and everybody is just amazed at how active I am, while I look at myself and see an 80% reduction in capability.

And of course, I wrote that paragraph prior to this week’s indoor track session, which turned out to be a bust. I had overestimated my progress, and started off with too much running on not enough pain medication, and after a few laps had pain and an insatiable urge to pee, even though I just went a moment ago and my bladder was far from full. So I’m in the bladder penalty box for now, when I recover in a day or so I’ll go back to walking which I’ve been doing recently with increasing success.

But hey, I’m still here, still moving, and still able to cover short distances at a genuine run! I’d like to give a shout to a couple of my “fans”. First is Jen, who unknown to her is the head of my cancer battle PR department, for her dedication to always getting an action shot of the two of us at the indoor track (from last week):

Also my sister, for texting me an amusing, personalized cartoon to commemorate my running during treatment. Yes, I do love these drugs, they are allowing me to continue living life and telling a good story along the way:

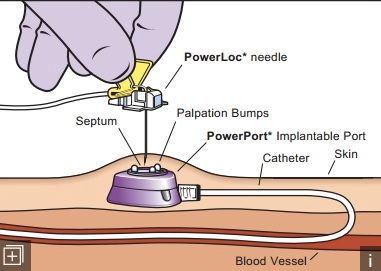

And finally, for reasons I can’t really explain I feel a need to close with a topless photo of myself, showing what cancer treatment has done to my body. Starting at the bottom, my right hand is pointing at a little green dot tattooed onto me and used as an alignment mark during radiation treatment back in 2018. The first three fingers of my left hand are pointing to the incisions made when installing my port. They look like I just scratched myself in the photo, but they're scars which trace the path of the tubing from my port, up and over the collarbone and into a vein. The pinky finger is pointing directly at the port, which looks almost like a third nipple. Good luck getting that vision out of your head. And finally, my chemo-fro hair do, which is still curly from the first chemo treatments. I’ve let it grow completely wild, expecting it to fall out again in a week or two.

Some people may look at this photo and remark at the muscle atrophy caused by androgen deprivation therapy, but no, I've always been scrawny like that.