The Battle Begins

Within 24 hours of writing this, I’ll be having the first infusion of my second course of chemotherapy. Compared to my first course, this will be a completely different cocktail of drugs, for what is effectively a completely different cancer. It will be the first meaningful shot fired by the good guys in cancer war 2.For those unfamiliar with chemo, treatment is scheduled as a series of cycles, with each cycle usually lasting 3-4 weeks. At the beginning of each cycle the chemotherapy drugs are given, and then during the rest of the cycle the body is given a chance to recover before the next cycle. And generally, it’s the bone marrow and associated blood counts that take the majority of the collateral damage, which limit the drug dosages, and determine the time between cycles.

My cycle will begin with three consecutive days of infusions. On the first day I’ll be given a pre-treatment of diphenhydramine (Benadryl), dexamethasone (a steroid), famotidine (Pepcid), and if I recall correctly ondansetron (anti-nausea). These are all intended to suppress allergic reactions to the chemotherapy and limit the initial side effects, and they work very well. I’m particularly a fan of dexamethasone, as it generally makes me feel like superman for a few days. Last year, dexamethasone is the reason I was able to go running around the indoor track the day after a chemo infusion. When it wears off the side effects hit like a bomb.

After the pretreatment comes an infusion of Carboplatin, which is basically a platinum atom with a few other atoms attached to help shepherd it through the system (don’t quote me on that explanation, it’s probably wrong). In this context, platinum is a heavy metal that is toxic to all cells, and shows a slight propensity for accumulating in cancer cells. This has been around for decades and is very effective treatment if a bit nasty in terms of side effects. It’s the Rambo of chemotherapy drugs, “his job was to dispose of enemy personnel... to kill, period! Win by attrition”

That will be followed by an infusion of Etoposide, which is another old chemotherapy drug. It interferes with the copying of DNA during cellular division and effectively kills any cells that try to divide (again, don’t quote me on that explanation). This is where chemotherapy can be a bit counterintuitive. It is more effective against cancers that are growing and dividing at a faster rate. Because more of the cancer cells will try to divide while the drug is present, a larger percentage of the cancer will be killed. Slower growing tumors are able to resist treatment simply because the cells are not as likely to divide during treatment.

And finally, I’ll get an an infusion of Atezolizumab which is a relatively new immunotherapy drug. Here’s my weird way of describing how it works: Healthy cells express a protein called PD-L1 on their surface that functions as a name tag. They say “I am Tom”. The immune system sees the name tag and doesn’t attack the cell, because attacking “Tom” cells would be an auto-immune disorder. This is also referred to as an “immune checkpoint”.

Some cancer cells are able evade the immune system by covering themselves with multiple name tags. “I am Tom” stuck on the front, back, sides, and top. There’s no way for the immune system to look at this cell and not thing it’s a healthy Tom cell. What the drug does is effectively rips the name tag off of all cells, allowing the immune system to go after the cancer cells, and possibly perfectly healthy Tom cells. To put it more scientifically, the drug is a PD-L1 antibody, and is in a category of drugs called “checkpoint inhibitors”, because they remove the checkpoints that prevent the immune system from attacking.

This all adds up to about 3-4 hours hooked to an IV having chemicals pumped into my veins. I’ll make sure to have my phone and tablet fully charged. At to that the 2+ hours driving to the office and back home afterwards, plus any time stuck behind school buses and general commuter traffic delays. It’s gonna be a long day.

On both Tuesday and Wednesday I’ll get another infusion of Etoposide and some amount of pre-treatment depending on how well I tolerated the infusion on Monday. This will go much faster, and probably be only a 90 minute visit.

That’s three days of infusions, probably about 6 hooked to an IV, another 6 hours of riding in a car, and however many hours and days of side effects once the supporting drugs wear off. This week my battle with cancer will be a full time job.

After that I’ll get two to three weeks of recovery time, depending on how fast my blood counts recover, to get ready for the next cycle. Repeat for six cycles, and I’ll be doing this until around July. After that, I’ll continue to get the Atezolizumab infusions regularly as maintenance therapy.

Surgery Report

Last week I had surgery to install a power port (no, I can’t charge my cell phone with it) and what is called a double-J stent. Let’s start with the stent. No, wait, let’s back up a couple weeks to my liver biopsy.An interesting aspect of the human body is that if you stick a rather large bore needle all the way into the liver to take a tissue sample, when you pull the needle out the flesh will close around the hole left by the needle and in a very short amount of time will seal the hole and begin the healing process. There’s no need for stitches or glue or other such wound closures if the hole is small enough.

I was fully expecting the urinary stent would be inserted from the “bottom up”, with my urologist going into the bladder via the only entrance that doesn’t require an incision, finding the blocked ureter, and forcing the stent in. Unknown to me, my doctors have been talking amongst themselves again and decided this was a better job for an interventional radiologist.

Until a few weeks ago I never knew there were interventional radiologists. They use radiology (CT scans, fluoroscopy, etc.) to guide them through medical procedures such as placing a biopsy needle right into the middle of a liver tumor.

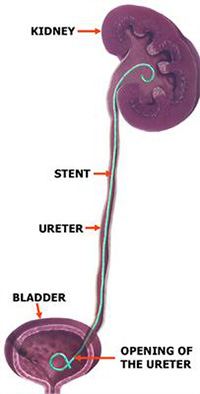

For the stent, fluoroscopy would be used to poke a needle into my backside and into the portion of my kidney where the urine collects, sort of like sticking a straw into a juice box. Then a wire would be passed through the needle, down the ureter, and into my bladder. The stent is then pushed over the wire and follows it down into my bladder. When the wire is removed, the ends of the stent coil up (thus, “double J”) and help hold the stent in place. If everything went well the needle would be withdrawn and my body would close up and begin healing with the stent left inside. If not, the needle would be hooked to an external nephrostomy bag to collect the urine produced by that kidney which couldn’t find its way down to the bladder.

As I noted earlier, this plan was created by my doctors without anybody telling me. The first I heard about it was from the poor innocent nurse who was giving me the boilerplate explanation and disclosing the possibility that I might end up with a nephrostomy bag. You could say I broke down at this point, but for the purposes of better story telling I metaphorically jumped up like a scalded cat and dug my claws into the ceiling.

Of course, having been through a similar scenario just a couple weeks ago with the biopsy I expected the radiologist to be able to peel me off the ceiling and explain everything. I know now that numerous e-mails were exchanged discussing my case, and my urologist thought it would be difficult for him to get the stent in place entering from the bladder, so deferred to the integrative radiologist. He said nephrostomy bags are relatively rare, and he usually can tell from the scans when one might be needed, and didn’t see anything in my scan that would pose a problem

I like my medical team, but patient communication definitely gets a “needs improvement” mark. Still, if their time is limited I’d much rather they spend it talking amongst themselves and making good decisions than keeping me informed. As has happened twice in the past three weeks, I’ll find out about the change in plans and recover, eventually.

And in the end, the stent went in easily, no nephrostomy bag for me!

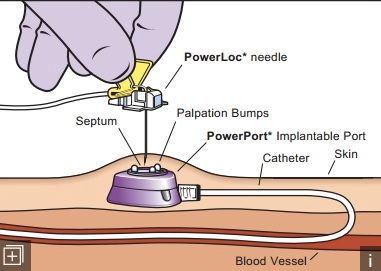

On to the power port. This is a device implanted under the skin that consists of a tiny reservoir for receiving chemotherapy drugs connected to a somewhat major vein at the base of my neck. Compared to finding a vein in my arm for an infusion, the port is the proverbial broad side of the barn. You can’t miss it. Also, because it goes into a bigger vein than those in my arm, the drugs are instantly diluted to a greater extent and less like to burn the vein. After multiple missed veins and two burned veins in my previous course of chemotherapy, I’m looking forward to having a port this time.

In the end that went well, and I’m slowly getting used to having a bump in my chest and what feels like a string connecting it to the base of my neck.

After the Surgery

I expected miraculous improvement after surgery, mostly because ignorance is bliss. Just two weeks prior I underwent a liver biopsy and then the very next day walked and ran a combined three miles at the indoor track. This surgery was going to finally unblock my kidney, how is that not going to make things instantly better?The good news is that it did instantly stop the bouts of severe, kidney stone levels of pain that could last for several hours at a time and didn’t respond to any pain medication available to me. As a human being I’m very pleased with that. As a runner, I haven’t even been able to walk a mile since the surgery, so fitness fanatic Tom is a bit disgruntled.

Let’s back up a few months. In October I ran a half marathon and didn’t need to stop once to take a pee. After the race I wanted to ramp up my mileage and try to complete a 15 mile training run before the end of 2019. That didn’t happen. The weather got colder, and my bladder got very sensitive to running.

As a result, every mile or two I’d have to hide behind a tree and relieve myself. Urination was becoming increasingly painful during this time. There was snow on the ground so hiding behind a tree meant getting my feet cold and wet. All this sapped the joy out of running. By the beginning of 2020, running caused blood in my urine, and that’s when the doctors started getting interested in my symptoms.

So my running had been reduced to mostly walking, and distances were reduced to two to four miles. Somehow, I magically thought a urinary stent would allow me to go right back to running 10 miles at a time. But no.

If you asked me, the purpose of the stent was to improve my running. I’m sure if you asked my doctor, he’d say something more along the lines of it was intended to restore kidney function, which is vital when he’s about to pump bag after bag of toxic chemicals directly into my bloodstream. The sheer fluid volume would otherwise exacerbate the pain and the kidney damage. Worse yet, reduced kidney function might limit clearance of the drugs and increase toxicity.

Still, I’m human, and I’m bummed that the stent is going to interfere with my running. There’s two problems the stent poses:

First is that the stent has exacerbated the painful urination. Previously, I would have rated the pain at 10, or “worst imaginable pain”. It seems I lack imagination. The current pain I feel urinating is indescribable, but I’ll try to describe it anyway. Imagine the worse muscle cramp you’ve ever had. That’s what my bladder feels like trying to squeeze out the last few drops of urine, and that’s probably more due to the cancer than the stent. Now, imagine that as the bladder is cramping and squeezing, it’s also impaling itself on the foreign object that is the stent.

I generally pee sitting down now, because it’s difficult to stand upright when the pain hits. I’ve developed a preference for the handicapped stall in public restrooms, because I can grip the handrails tightly and help hold myself on the toilet. Like Spinal Tap, my pain dial now goes to 11. On the bright side, this only lasts for a minute or so.

The second problem with the stent is that even when I’m not peeing it’s still generally irritating my innards, and activity makes it worse. I suspect my body will get used to it, and perhaps even build up internal callouses to protect itself. But at this point, I don’t know how much walking or running I’ll be able to do with the stent in place. I may have to wait for treatment to shrink the tumors to the point where the stent can be removed before resuming copious levels of activity. I expect I’ll be able to do quite a bit by normal person standards, but not by marathon standards.

So to bring this lengthy post to a quick end, chemotherapy starts tomorrow and let’s all hope that shrinks the tumors and makes life with the stent a little more bearable in the near future.

No comments:

Post a Comment